Seismo Blog

The Missing Link

Categories: Bay Area | Hayward, Rodgers Creek | Earthquake Faults and Faulting

November 18, 2016

It has long been suspected, but scientists could not be sure. Are two of the most dangerous earthquake faults in Northern California, the Hayward Fault and the Rodgers Creek Fault, separate entities or are they connected in some way? The answer to this question lies literally in the mud. It is hidden in the invisible geology under the murky sediments of San Pablo Bay, the northern extension of the San Francisco Bay. San Pablo Bay, with its almost circular shape, separates the narrows between Point San Pablo and Point San Pedro just north of the Richmond Bridge from the Carquinez Strait, through which the Sacramento and the San Joaquin rivers bring their freshwater supplies from further east. Research just published in the journal Science Advances suggests very strongly that the missing link between these two faults has been found. The Hayward and the Rodgers Creek Faults have now to be considered as one more than 110 mile long fault.

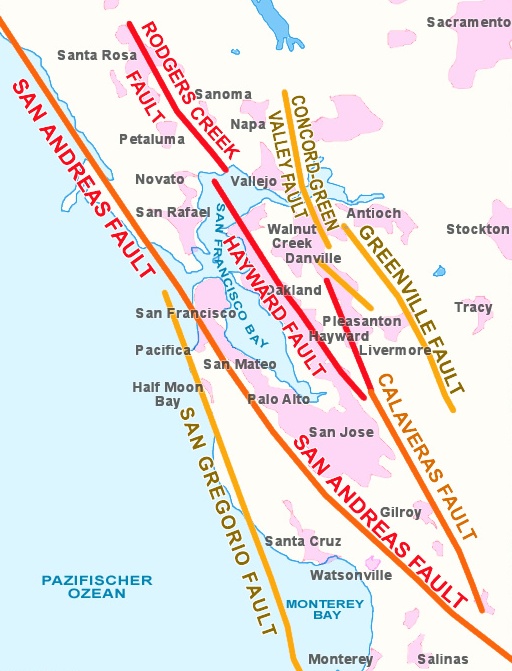

Figure 1: The Earthquake Faults in the Bay Area

In Northern California, the tectonically very active boundary between the North American plate and the Pacific plate takes a peculiar shape. Instead of expressing itself in just one fault line, it is split up into a wide system of a dozen or so parallel faults. This system extends in an east-westerly direction for almost 50 miles. The westernmost fault is the San Gregorio, which runs mostly offshore. It merges with the San Andreas at Stinson Beach. At this location the San Andreas fault resurfaces and reaches land after having vanished from sight into the ocean near Mussel Rock off of Daly City on the Peninsula. Looking east, the next fault in this system is the Hayward Fault. It runs along the foot of the East Bay Hills from Warm Springs near Fremont to San Pablo Bay. Even further east lies the Calaveras Fault, which extends from Hollister in the South into the 680 corridor towards Danville and San Ramon. Finally, east of Mount Diablo and east of Livermore, the system terminates with the Greenville Fault.

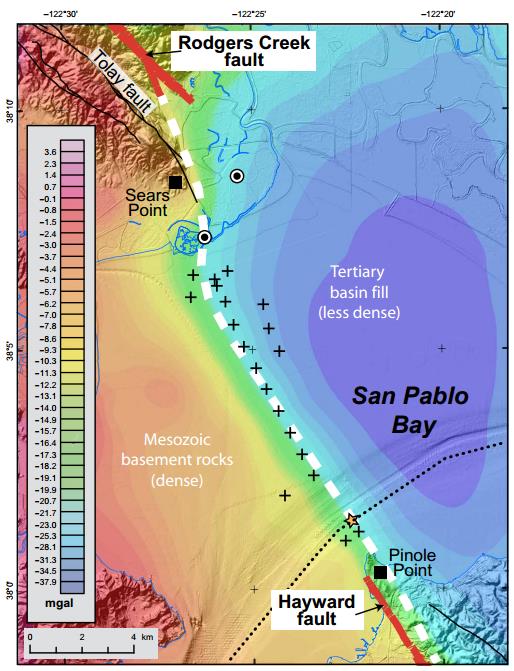

Figure 2: Hidden under the mud of San Pablo Bay: This gravity map show a clear demarcation line between the marine sediments in west (brown color) and the sediments in the east (blue color). The continuous line between the two areas is the missing link between the Hayward and the Rodgers Creek Faults. (from Watt et al., 2016)

A similar system of parallel faults exists north of the Bay with - from west to east - the San Andreas, the Rodgers Creek, the West Napa, and the Green Valley Faults. It has long been established that the Green Valley Fault is linked to the Concord Fault further south with a geologic connection under Suisun Bay. But it has been unclear until now if there was also a link between the Hayward and the Rodgers Creek Faults. Looking at a map, the northern end of the Hayward Fault is at Point Pinole. In contrast, the southern end of the Rodgers Creek Fault enters San Pablo Bay just east of Sears Point. If you continue to draw each fault into San Pablo Bay, they would be separated by less than two miles - a very small distance on a plate-tectonic scale.

A group of researchers from the offices of the United States Geological Survey in Menlo Park and Santa Cruz lead by Janet Watt have now solved the longstanding mystery. Using the small research vessel Parke Snavely the team crisscrossed San Pablo Bay and used seismic techniques to remotely investigate the geologic structure under the bay mud. In addition they measured minute changes in the gravity and magnetic fields along the profiles. After more than a year of careful analysis, the group recently published their conclusions: They found a clear link between these two faults hidden under the bay mud.

This result is not only of esoteric academic interest. It actually changes the seismic hazard for the eastern section of the San Francisco Bay Area. Until now, the Hayward Fault was considered a 75 mile long continuous fault. The worst earthquake that could have happened along this stretch would have broken the whole fault, resulting in a magnitude slightly above 7. The Rodgers Creek Fault, with its length of 39 miles, carried a smaller seismic hazard, because if it had ruptured in its entirety during a quake, it would have produced a quake with a magnitude of less than 6.5.

A rule of thumb: The longer the rupture length of an earthquake, the higher its magnitude will be. The combined Hayward-Rodgers Creek fault has a length of more than 110 miles. Because the faults are connected, an earthquake starting on one fault could easily continue along the other. Hence the combined Hayward-Rodgers Creek Fault is capable of delivering a big punch of a magnitude 7.5 or larger quake. It will affect not only the East Bay but also the Wine Country all the way north to Healdsburg. (hra131)

The research paper can be found in Science Advances under doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601441

BSL Blogging Team: Who we are

Recent Posts

-

: Alerts for the Whole West Coast

-

: Destruction in the Eastern Aegean Sea

-

: An Explosion in Beirut heard all over the Middle East

View Posts By Location

Categories

- Alaska (3)

- Bay Area (24)

- Buildings (3)

- Calaveras (4)

- California (13)

- California ShakeOut (3)

- Central California (4)

- Chile (4)

- Earthquake Early Warning (10)

- Earthquake Faults and Faulting (44)

- Earthquake Science (3)

- Haiti (3)

- Hayward (12)

- Indonesia (4)

- Induced Seismicity (3)

- Instrumentation (18)

- Italy (6)

- Japan (7)

- MOBB (3)

- Mendocino Triple Junction (5)

- Mexico (7)

- Nepal (3)

- North Korea (5)

- Nuclear Test (5)

- Ocean Bottom Seismometer (3)

- Oklahoma (4)

- Plate Tectonics (18)

- Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards (16)

- Salton Sea (3)

- San Andreas Fault (14)

- Seismic Waves (13)

- Seismograms (4)

- ShakeAlert (3)

- Southern California (5)

- Surface Waves (3)

- Today in Earthquake History (20)

- Volcanoes (4)

- subduction (3)